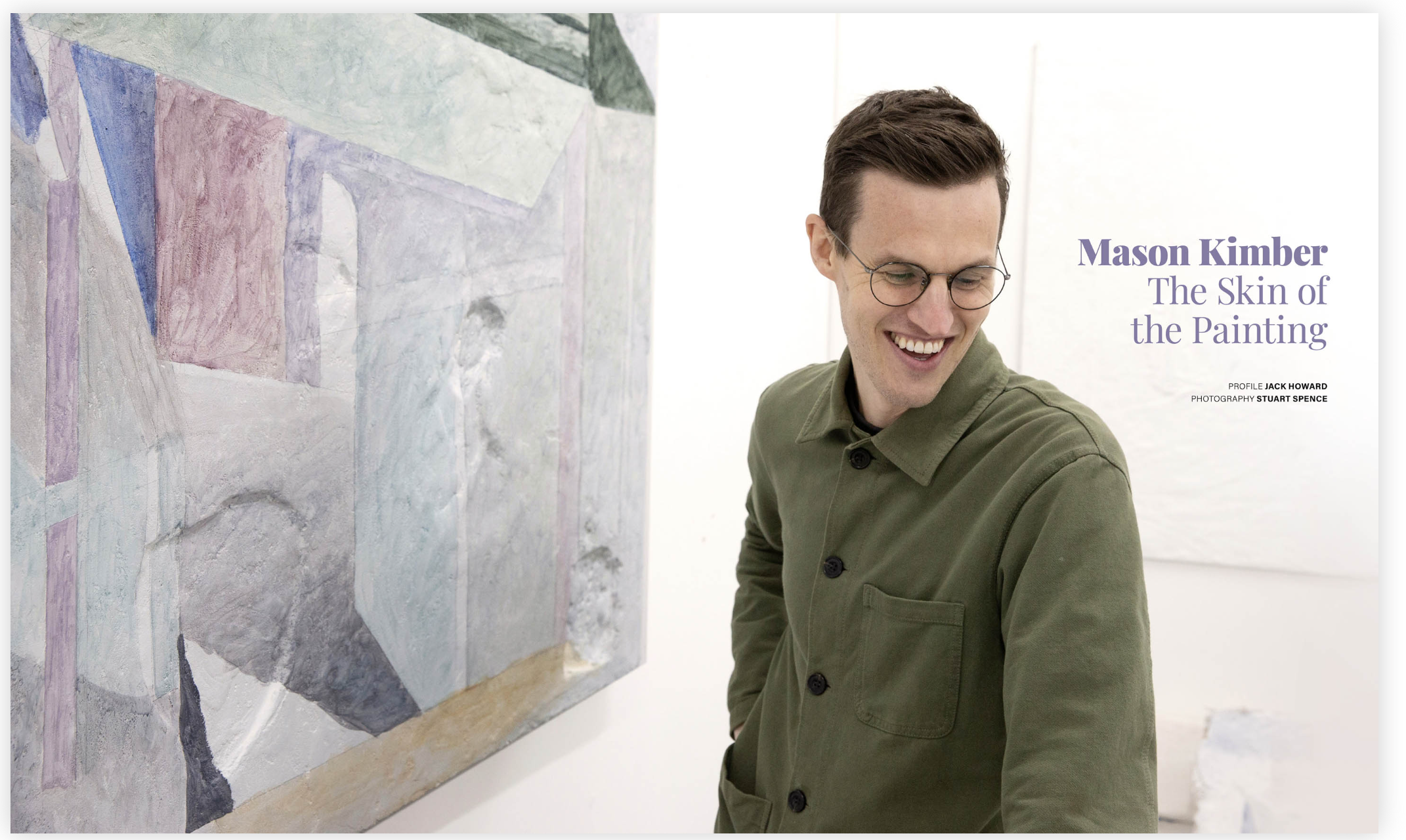

by Jack Howard

Artist Profile - Issue 72

Mason Kimber’s newest paintings mark the artist’s furthest explorations yet into what he describes as “spatiality in painting.” Ahead of his first institutional solo exhibition, Kimber reflects upon a half-decade of work that draws together informal currents of materiality, haptic visuality, place and memory.

At his Leichhardt studio, Mason Kimber shows me a cache of photographs taken of a Perth nightclub, owned by Kimber’s father, in the 1980s and 1990s. The club had many names and many looks—including a Bat Cave and a Shark Bar—all designed from his father’s outsized imagination. Kimber remembers being taken to the club by his father during daylight hours, seeing the days-before and mornings-after of a place only known to its patrons in the darkness.

An image of a ladder on a clad, textured wall revives Kimber’s childhood memory of climbing to reach the club’s DJ booth. Now an artist drawn to the creation of similar surfaces made of modelling compounds and extruded polystyrene—and a DJ himself to boot—it is difficult not to psychoanalyse and read deterministically Kimber’s creative life through these records of formative encounters.

Drawings derived from these photographs and memories are pinned to the studio walls. They are not representational sketches of the club, nor even compositional rehearsals—for Kimber, drawing is instead a way of “homing in on the spatial dynamics of a surface.” What that space is inhabited by and constructed from—light and shadow, weight and lightness, interior and exterior, movement or stasis—remains open to Kimber’s process.

I ask if Frank Hinder is a possible influence, thinking of the spatial push and pull in his depictions of metropolitan Sydney (as in Kaleidoscope Tram, 1948). Kimber replies that Godfrey Miller is closer to hand, though with differing commitments to “compositional scaffolds” and handling of the numinous. Nearer still, perhaps, is Elwyn Lynn, whose attention to materiality, textural surfaces and general informality is on a wavelength similar to Kimber’s own.

In August, an exhibition of Kimber’s recent works made between 2021 and 2025 will be on view in A Caressing Gaze at University of New South Wales Galleries, Sydney. The show’s title is drawn from film theorist and philosopher Laura U. Marks whose work Kimber incorporates into his nearly completed doctoral thesis. Marks—in her book The Skin of the Film, 2000—draws on the work of prior theorists (Aloïs Riegl, Henri Bergson, Gilles Deleuze) to define twin concepts of “optical visuality” and “haptic visuality” in cinema.

Optical visuality refers to the idea that the visual cues of images are sufficient in themselves for an audience to comprehend them, as in most narrative films. But a more complex function of cinema is where images are interpreted by senses other than sight. Marks describes haptic visuality as one such example, where “the eyes themselves function like organs of touch.” Kimber is drawn to this idea, in particular Marks’s note (also from The Skin of the Film) that haptic visuality “is more inclined to move than to focus, more inclined to graze than to gaze.”

Haptic visuality in painting is an established concern. Marks refers to Dutch still life as an example from the visual arts where the eye is left to skate across an array of surface effects—the pocked rind of a lemon, the slime coat of a fish; cool, polished silverware, or silken fabrics—in addition to or, at times, in place of substantive forms. It is a specific example of a tradition that involves, as Marks puts it, “intimate, detailed images that invite a small, caressing gaze.”

Tactility, surface and place have formed a dominant part of Kimber’s practice over many years. While visiting his wife’s family in the Philippines in 2018, Kimber made his first use of silicone moulds, made from pressing a malleable putty into architectural surfaces around Quezon City. From there to his Strata works, 2021, and casts made from the colonial fixtures around the National Art School—where he completed his master of fine arts and continues to teach—mould-making has become essential to Kimber’s practice. With each casting—supported by chance interventions in the pouring, breaking and recontextualising of each fragment—these negatives of surface textures can draw direct, situational and narrative connections between mould, cast and artwork.

But Kimber’s newest works are distinct from prior series in that the “origins” of his moulds have become incidental. “I’ve come to embrace the alchemy of the studio,” says Kimber, “like a witch’s cauldron.” Cast fragments, now, are more “like a memory” than an index—a fitting evolution to contend with the challenge of connecting spatially with his father’s long-since closed nightclub.

Kimber is a painter, though since mould-making entered his practice, it is arguable that either sculptural relief or abstract painting has stood forward in any given work or series. In his recent Tablet works, 2023, there is more of a shared stage for these elements—with relief acting as a frame for abstract paintings concerned with the behaviour and quality of lens flares and other light effects.

In his latest works from 2025, Kimber has solemnised this “marrying of painting and relief.” Where earlier works had alcoves for fragments to nest, or frames that housed painted surfaces, like frescoes in a cathedral, entire surfaces are now relief and painting together. Kimber makes his supports by hand from a range of materials, including hessian, paper pulp and plaster. Like the lunar surface, there are craters where mould-cast fragments used to sit before being removed by the artist. These indefinite, untraceable absences have been (not without violence) excised and blurred over, like the tide washing over footprints in sand.

Over the pocked and varied surface of this material topography, reliant on the preparatory mapping undertaken in his drawings, Kimber paints. The “spatiality in painting” that results is more abstract than the reckoning of translating the world of three-dimensions into two practiced by representational artists. Instead, it is a way of getting at surface by seeing it in haptic terms. The eye may, momentarily, settle upon a divot or a bump for contemplation, as it might over a passage of colour or an exposed pencil line—but the space within and of each painting is kinetic, and the feedback with the viewer highly tactile.

All artists want the attention of a viewer, but few artists articulate in their work the conceptual basis of that attention. Kimber’s paintings relish in each articulation of haptic visuality, inviting us all to brush against the textural and material world of surface—much as the eyes of a certain child might have done when surveying the nightclub created by his father over thirty years ago.

-

Exhibition Review, Lustre

by random_re_view

August 2022

Mason Kimber @sophiegannongallery presents works that signal a significant shift from what we’ve oft known about his work. The plastery palette has exited, his ghostly archeological traces & embossed facades now embedded in warm diagrammatic fields of odd angle & disorientating perspective. The palette is closer to the honeyed tone that we might find in a type of now unfashionable landscape painting, though these are unlike any landscapes you would be familiar with. Instead, the view is mostly downward, all raking shadows over footpaths, truncated doorways & portals, and sunnily caressed surfaces, forensically noted. Where his previous panels were an epitome of complex charms, these new works are less immediately attractive but more strange & dreamlike, demanding of patience rather than the fleeting glance. Analytical Cubism comes to mind - its fracture a model marrying multiple viewpoints, odd geometric, slipping planes, and stylized quasi-decorative spotty ‘fill’ which could so easily be cloying yet is anything but - evoking Braque & Picasso’s early hi-jinks in competitive oneupmanship. A relative shift in implied scale adds a certain expansive weightiness, whilst the essentially archaic nature of his work remains, Kimber testing his own history with a newly toughened result.

-

Mason Kimber, Lustre

by Vanessa Berry

Catalogue text, Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

July 2022

Across the city there moves a softer architecture. Light and shadow, dust and dry leaves, water over sandstone. When we go out walking we move across it too, past building sites hidden behind scaffolding, warehouses converted into apartments, and rows of narrow houses pressed shoulder to shoulder. This is the pattern of the inner-city, older and newer side by side, the urban flux of stagnation and renewal.

Along the way our attention is drawn to details and textures, impressions that have lasted for longer than their moment. A cracked pane of leadlight glass, a mistaken step into wet concrete preserved as a footprint, or the rough-cut blocks of a weathered stone wall. We look for them every time, markers of a trail that extends through our local streets. Each is a past action or gesture, remembered in the present through these traces.

Nothing here is permanent, but on some afternoons, when the light turns gold and shadows stretch, time slows almost to a halt. If we are out walking, we stop at the street corner. At home, we pause at the window. The only thing that moves is our eyes, which follow the edges of shadows, seeing them as new shapes, elongated and intermingling.

In this long and contemplative moment, fragments recombine, drawing out memories of other places and times. This shape is the memory of a first walk through an unfamiliar city when every detail seemed to have its own life. This one is the comfort of returning to a place well known. This shape suggests the cool of a stone floor, this one a high window that frames a slice of sky. This shadow is an arrangement of shells and stones, and this one a silhouette of branches that extend over an interior wall, so the outside is shadowed within.

As much as we can excavate a city's histories, other ways of knowing come lightly, in temporary scenes and chance arrangements, in surfaces and textures. This is what Lustre captures: another way to understand places and how we inhabit them.

-

Capturing the memory of place: Mason Kimber

by MCA Australia

Stories & Ideas: Video

16 November 2021

-

Mason Kimber, Strata

by Neha Kale

Catalogue text, Kronenberg Mais Wright, Sydney

February 2021

Cities are easily dismissed as inanimate, stony witnesses to the lives that pass through them. But walls and ground and pavements are living organisms, as marked by history and experience as human skin.

When I think about the past, faces are blurry. But I remember peach-coloured paint, flaking off my grandparents’ Bombay apartment, Roman rubble near a London tube stop and Triassic-era sandstone cliffs under a Sydney bridge with a startling acuity.

To recall these surfaces is to embark on emotional archaeology. It’s to unearth childhood awareness, the promise of twentysomething adventure, the flashes of awe that are part of regular adult life.

In literature, ‘memoir’ stems from the French for aid-memoire – a device that helps you remember. Mason Kimber made the works in Strata, which owes its name to a Walter Benjamin essay, during walks around his former neighbourhood, near Forbes Street, Darlinghurst.

The artist alighted on interesting surfaces: a drain cover, referencing a 19th century plumbing company, a texture as cranial as a sea sponge on the face of a sandstone brick.

Kimber cast gypsum to each site. But his mould would snap as he pried it off, creating a sense-impression that was also a record of his encounter. In the studio, the artist housed these fragments in wall-based panels, manifesting his memory of each place by reworking his material.

Strata’s sculptural reliefs reflect the ways in which we are shaped by the places we move through. But for Kimber, making memories isn’t a passive process. It’s an act of excavation. We get to know ourselves by looking closely at the world around us, understand what lies beneath the surface by giving the surface itself a physical form.

-

Collectors Love - Mason Kimber

by Sharne Wolff

Art Collector Magazine - Issue 91

January 2020

Mason Kimber is interested in capturing the traces of memory found lingering in architectural spaces. Graduating with a Master of Fine Arts in 2013, Kimber has held a solo show in every year since. His first outing with Sophie Gannon Gallery in Melbourne was 2018’s Future Relics, where the gallery reportedy sold the majority of the show very quickly, some to earlier devotees and some to clients who were previously unaware of Kimber and his practice. Afternoon, Kimber’s most recent exhibition of fresco works, was a comlete sell-out.

A continuation of his curiosity in the materiality of surfaces, Kimber’s frescoes were based on digital collages and comprised a mixture of acrylic, sand, lime plaster and polystyrene on wood. While the works ooze the easy pleasures of the afternoon light, they also reflect Kimber’s interest in revealing the deep alliance between cognitive thought and place. Gallerist Sophie Gannon suggests that “Mason’s work is firmly grounded in traditional artistic methods (through his use of fresco, painting and sculpture) yet his approach and aesthetic is distinctly contemporary. He also explores timeless themes of memory, one’s connectedness and the physical spaces we inhabit - which is why I think his work resonates with curators and contemporary collectors.”

Making exciting strides in his practice, Kimber has recently started making sculptural reliefs - several of which were exhibited at Spring 1883 in Sydney last September, and selected for the 2019 Churchie National Emerging Art Prize. An extension of the frescoes, Kimber reveals that these new works began as studio experiments. Beginning with broken parts of painted frescoes cast into tablets, he found that “by rendering these objects into a single flat colour, they transform into unified sculptural forms rather than paintings...” adding that he enjoys “the idea of moving between pictorial and sculptural concerns”.

In late 2019, the Sydney-based artist headed to France to undertake a performative scultural commission with Paris’ Galerie Allen. The work was included in Prologue I, a multisite group exhibition that aired in December. Following his 2017 exhibition Arcades - made in homage to german literary critic Walter Benjamin’s incomplete 20th century Arcades Project - Kimber’s Paris project involves a site-specific sculptural installation that captures the shared histories of the local shopkeepers in the Passage du Prado - one of the few remaining Paris arcades. Through this collaborative process, Kimber aims to weave collective narratives and, as he puts it, “reconfigure the way that we engage with history by listening to local stories, translating them into sculptural forms [to capture] a living sense of place”.

-

Surface Activations

by Mason Kimber

ADSR Zine - Issue 10

August 2020

It’s one thing to observe a surface, but another to feel its presence. Much effort has been made recently to disconnect our touching bodies from the world around us: social distancing, masks, sanitization, isolation. The touching of surfaces has literally become a matter of life and death. As a studio-based artist who uses moulding and casting, this period has made me more aware of touching - not as a threat but as an intimate form of reading and understanding through material.

The process of moulding a surface involves slowly pressing silicone putty, which has the consistency of play-doh, into the crevices of an object’s skin. Encountering its topography with the tips of your fingers allows you to develop an intimate understanding of the object and its location. By physically tracing these details, I exercise a subconscious form of bodily reading and memory-making, resulting in a direct engagement with the felt qualities of the object: its composition and temporality within a larger timescale. With heightened awareness to the sense of touch, fingers replace the eyes to temporarily perform the role of vision. Like navigating a pitch-black room at night, you see instead with your hands.

After the mould hardens into thick rubber, it’s carefully removed to reveal two interrelated aspects of the site. The bottom side contains an almost perfect physical recording of the undulating texture beneath. In contrast, the top side tells the story of an encounter. Its forensic impressions trace the meandering fingers as they converse with the object’s surface, finding their way across it. A physical transcription of this conversation is captured, channeled through the silicone putty itself. What results is a literal timestamp of the surface and the performing hand as it seeks to memorialise a place.

After the mould is removed, the process of casting begins back in the studio. This next stage involves a different form of material encounter, one with the facsimile. Various casting compounds (gypsum, resin, wax, sand, foam) are poured and left to harden, producing a physical copy of the object in all its detail. However, my interest lies not in this faithful index, but rather in the experimental reworking of fragments and processes of emergence that a studio-based practice allows.[1]

One way to explore the inner qualities of an object is to provoke it and spring it into action. And the simplest way to achieve this is to break it. Usually, I use a hard tool, like a hammer, or I simply drop the casted object from a height and allow gravity to make the final call as a chance strategy. The pure act of breaking reveals certain behavioral qualities, similar to what architect Anne Holtrop refers to as “material gesture”.[2]

Art is capable of rendering the invisible forces of the earth into visible form by extracting fragments of these forces and containing or framing them within the materials of an artwork.[3] According to philosopher Elizabeth Grosz, one of art’s defining features is that it “enables matter to become expressive…to intensify—to resonate and become more than itself”.[4] Grosz’s understanding of artistic expression takes emphasis away from the determination of the human mind, and over to the inherent nature and forces held within matter itself. Testing these forces by observing and responding to a certain object’s breaking point can be an effective way to expose its inner resonance.

Once broken, it ceases to be an object and instead becomes a material. With objects, we usually attach an understanding of the stillness of form and make sure not to break them. Materials, on the other hand, are usually handled and allowed to perform and transform.[5] This slight shift of understanding opens the fragment up to further possibilities of reconfiguration or bricolage. In Claude Levi-Strauss’s idea of the term, a bricoleur “works with his hands in devious ways, puts pre-existing things together in new ways, and makes do with whatever is at hand”.[6]

By treating fragments as material to excavate and recompose, the artist positions themselves as a quasi-archeologist digging through ruins to uncover hidden forces. Instead of treating archaeology as something purely obsessed with the past, “the archaeological act thus becomes an engagement with the present’s surface: the mediation of the past as a creative engagement with the present and future”.[7] This same strategy of excavating and reconfiguring disparate fragments, or breaks is echoed in early hip hop music, enabled by the invention of the electronic mixer and sampler.

In recapturing, remixing and recasting fragments, a series of actions and gestures can accumulate and embed themselves on and within the growing material. This generative, conversational approach to making is contingent on the behavior of the materials themselves as they undergo transformations, from liquid to solid and back again. Forming into larger panels through a process of growth, it places the maker “as a participant in amongst a world of active materials”.[8]

By moving beyond the limiting view of the artefact as an object of human association, the history of the fragment is then seen as the history of forces, of activations. It reframes archaeology as an open, creative act rather than a purely historical one. Similar to the capturing of two corresponding temporalities within the silicone mould (surface and fingerprints), these processes both carry forth and reimagine the object’s past by recasting its traces firmly into the present.

[1] Grosz, Elizabeth. Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008, 1.

by Mason Kimber

ADSR Zine - Issue 10

August 2020

It’s one thing to observe a surface, but another to feel its presence. Much effort has been made recently to disconnect our touching bodies from the world around us: social distancing, masks, sanitization, isolation. The touching of surfaces has literally become a matter of life and death. As a studio-based artist who uses moulding and casting, this period has made me more aware of touching - not as a threat but as an intimate form of reading and understanding through material.

The process of moulding a surface involves slowly pressing silicone putty, which has the consistency of play-doh, into the crevices of an object’s skin. Encountering its topography with the tips of your fingers allows you to develop an intimate understanding of the object and its location. By physically tracing these details, I exercise a subconscious form of bodily reading and memory-making, resulting in a direct engagement with the felt qualities of the object: its composition and temporality within a larger timescale. With heightened awareness to the sense of touch, fingers replace the eyes to temporarily perform the role of vision. Like navigating a pitch-black room at night, you see instead with your hands.

After the mould hardens into thick rubber, it’s carefully removed to reveal two interrelated aspects of the site. The bottom side contains an almost perfect physical recording of the undulating texture beneath. In contrast, the top side tells the story of an encounter. Its forensic impressions trace the meandering fingers as they converse with the object’s surface, finding their way across it. A physical transcription of this conversation is captured, channeled through the silicone putty itself. What results is a literal timestamp of the surface and the performing hand as it seeks to memorialise a place.

After the mould is removed, the process of casting begins back in the studio. This next stage involves a different form of material encounter, one with the facsimile. Various casting compounds (gypsum, resin, wax, sand, foam) are poured and left to harden, producing a physical copy of the object in all its detail. However, my interest lies not in this faithful index, but rather in the experimental reworking of fragments and processes of emergence that a studio-based practice allows.[1]

One way to explore the inner qualities of an object is to provoke it and spring it into action. And the simplest way to achieve this is to break it. Usually, I use a hard tool, like a hammer, or I simply drop the casted object from a height and allow gravity to make the final call as a chance strategy. The pure act of breaking reveals certain behavioral qualities, similar to what architect Anne Holtrop refers to as “material gesture”.[2]

Art is capable of rendering the invisible forces of the earth into visible form by extracting fragments of these forces and containing or framing them within the materials of an artwork.[3] According to philosopher Elizabeth Grosz, one of art’s defining features is that it “enables matter to become expressive…to intensify—to resonate and become more than itself”.[4] Grosz’s understanding of artistic expression takes emphasis away from the determination of the human mind, and over to the inherent nature and forces held within matter itself. Testing these forces by observing and responding to a certain object’s breaking point can be an effective way to expose its inner resonance.

Once broken, it ceases to be an object and instead becomes a material. With objects, we usually attach an understanding of the stillness of form and make sure not to break them. Materials, on the other hand, are usually handled and allowed to perform and transform.[5] This slight shift of understanding opens the fragment up to further possibilities of reconfiguration or bricolage. In Claude Levi-Strauss’s idea of the term, a bricoleur “works with his hands in devious ways, puts pre-existing things together in new ways, and makes do with whatever is at hand”.[6]

By treating fragments as material to excavate and recompose, the artist positions themselves as a quasi-archeologist digging through ruins to uncover hidden forces. Instead of treating archaeology as something purely obsessed with the past, “the archaeological act thus becomes an engagement with the present’s surface: the mediation of the past as a creative engagement with the present and future”.[7] This same strategy of excavating and reconfiguring disparate fragments, or breaks is echoed in early hip hop music, enabled by the invention of the electronic mixer and sampler.

In recapturing, remixing and recasting fragments, a series of actions and gestures can accumulate and embed themselves on and within the growing material. This generative, conversational approach to making is contingent on the behavior of the materials themselves as they undergo transformations, from liquid to solid and back again. Forming into larger panels through a process of growth, it places the maker “as a participant in amongst a world of active materials”.[8]

By moving beyond the limiting view of the artefact as an object of human association, the history of the fragment is then seen as the history of forces, of activations. It reframes archaeology as an open, creative act rather than a purely historical one. Similar to the capturing of two corresponding temporalities within the silicone mould (surface and fingerprints), these processes both carry forth and reimagine the object’s past by recasting its traces firmly into the present.

[1] Grosz, Elizabeth. Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008, 1.

[2] "Material Gesture." Anne Holtrop, 2019, accessed 1 July 2020, https://holtrop.arch.ethz.ch/Material-Gesture.

[3] Grosz, Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth, 22.

[4] ibid, 4.

[5] Ingold, Tim. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London;: Routledge, 2013, 18.

[6] "Claude Levi Strauss’ Concept of Bricolage." Literary Theory and Criticism, 2016, accessed 22 July 2020, https://literariness.org/2016/03/21/claude-levi-strauss-concept-of-bricolage/.

[7] Harrison, Rodney. "Surface Assemblages. Towards an Archaeology in and of the Present." Arch. Dial. 18, no. 2 (2011): 160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203811000195.

[8] Ingold, Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, 21.

-

Fig. 1 Pressing the silicone putty into the surface

Fig. 2 Fingerprints embedded within the silicone

Fig. 3 Casted fragment (before being broken)

Fig. 4 Broken fragments embedded within layers of casted material

Mason Kimber - Interview

by Simek Shropshire

Floorr Magazine - Issue 20, London

13th June 2019

Featured in your exhibition Slanted Memories at COMA, Sydney, were a series of sculptural tablets that were reminiscent of Greco-Roman marble sculptures, particularly the ornamental reliefs and frescos that adorn the facades of ancient temples. Alongside the inspiration you gleaned from a trip to Quezon City, Philippines, was there a classical influence in this most recent body of work?

My interest in ancient reliefs and fresco painting stems from my 3-month studio residency at the British School at Rome in 2014, which continues to influence the work I make. My research proposal for that residency was based on the concept of ‘architectural memory’, and Rome is an obvious choice because of its many visible layers of history.

I became obsessed with the broken materiality of frescos and their direct connections to a past era. There are so many examples in Italy where art, design and architecture were integrated into a unifying system. Fresco painting itself is a mixture of painting, sculptural relief and architecture. Regardless of location or era, I’m interested in the history that is stored and embedded within the surfaces of things, and how buildings can hold memories and emotions within their skins.

Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your background? Where did you study?

I was born in Perth, Western Australia and did my undergraduate studies at Curtin University. After living in New York for a year, I moved to Sydney to do an MFA in painting at the National Art School, where I now work as a casual teacher in the painting department.

Most people in my family are entrepreneurs and self-starters, so I grew up in a supportive environment and was encouraged to follow my passions. Looking back, I realise that my leanings towards art can also be traced back to my grandfathers. The one on my father’s side started painting when he retired and taught me traditional painting techniques as a kid. When I was a teenager, my mum revealed to me that I had another grandfather who was an artist and he was associated with the Neo-Expressionist movement in New York during the late 70’s and early 80’s. I discovered he was also a figurative painter making works about memory, and I ended up visiting him in the Hudson Valley, where he still lives.

Throughout your career, you have exhibited paintings and wall-based reliefs that contain collaged, fragmented elements. Some paintings themselves exist as fragments of a whole, such as the frescoes in your exhibition ‘Oltre la Vista’ in which each painted scene has been partially chipped away from the plaster. What are your intentions behind such elemental fragmentation? How do you conceive of fragmentation in relation to memory and recollection?

The beauty of a fragment is that it never contains a complete story. The viewer is invited to speculate on what’s missing and fill in the gaps themselves. It’s this idea of leaving room for the audience.

When making those fresco works, I realised that by almost destroying the painted image it actually opened things up. What’s left is a feeling for something that was once there, a residue of previous gestures and hints of the past. A fragment of something can speak much louder than the whole. The key is to find that sweet spot where just enough visual information is given without revealing the entire story.

I see memory as fragmentary by nature. There are details of my childhood house that appear vivid, such as the concrete floors and blue metal wardrobes, while other aspects of it remain obscured. This speaks to the way that images are recalled in the mind; it’s necessary to focus on some details and forget others. Images of past memories can remain scattered unless they’re given a location or room. It’s said that doorways can destroy memory, so the moment you pass through an architectural threshold, a signal is sent to the mind that a new scene has begun, and that it’s time to refresh. I’d like to think that my wall tablets serve as new homes for lost memories.

Stone/Cloud, 2019

You have stated, “My intention is not to recreate the physical exactness of a space or object,’ Kimber says, ‘it’s about capturing their memories and tangible qualities, and turning them into monuments to stories that are worth preserving.” Would you classify your paintings, reliefs, and installations as mnemonic artefacts? If so, what does it mean for these works to serve as archives of memories that may not be your own?

Mnemonic artefacts - that’s a great way to describe them! Memory is never factually accurate or wholly authentic. Instead, I think of memories as subjective fragments from the past that are constantly being re-invented or shaped by our own present circumstances. Because memories are rearranged in the mind, they can offer clues.

The surface moulds I cast are not just a straightforward copy of a place, instead they embrace the uncertainty of remembering. Through an intuitive studio process of breaking, marking, shaping and painting, I am able to insert my own visual language into the narrative of the original object. The work becomes a capsule of the past and present, an intermingling of personal and collective stories. Perhaps they could be thought of as shared archives of remembering?

Tell us a bit about how you spend your day / studio routine? What is your studio like?

I recently moved into Shirlow Street Studios, a new studio complex run by Art Incubator, a philanthropic program for Sydney artists. I have several casual jobs within the arts that sometimes take up my mornings, however most afternoons and evenings are dedicated to studio time.

My studio is divided into two rough zones: one for painting and the other for sculptural stuff, such as mould-making and casting. In recent years, the floor has become more important than the walls. I try to apply an archeological approach to painting, mining the remnants of objects and orphaned fragments scattered throughout the floor for potential future uses. Each contain their own layered histories and may go through years of iterations and identities before finding their final form or location. I like to keep this element of discovery, which is partly why I continuously break and remake fragments. It’s almost as if I’m searching for something that was always there, yet difficult to notice. They just needs to be mined and excavated to reveal their hidden potential.

The best thing about a studio-based practice is that you can think through making.

I prefer responding to things rather than importing my conclusions onto them. I think part of my roles as an artist is to empathise with these stranded objects and give them a new sense of belonging.

What artwork have you seen recently that has resonated with you?

I recently came across an exhibition online by Cayetano Ferrer titled ‘Memory Screen’ at Commonwealth and Council in LA. Ferrer casts remnant components of old buildings and uses them to layer and frame the gallery space in multiple ways. There’s many examples of artists that make casts of historical objects, however Ferrer’s work seems to emphasise and celebrate the fissures, slippages and breakages that distinguish the replica from the original. Combining fragments of LA’s historic architecture such as stained glass windows and archways from across periods, his incomplete, hybrid forms invite you to fill the gaps of what’s missing. These gaps also speak to the film sets of Hollywood, where scenic backdrops, replicas and CGI technology constantly blur the line between reality and imitation.

Is there anything new and exciting in the pipeline you would like to tell us about?

I’m most excited about a site-specific project in Paris’ north-eastern arrondissements called PROLOGUE I, held in conjunction with Galerie Allen, Untilthen, and KADIST Foundation, in November 2019.

I’m planning to make moulds and fragments of objects and surfaces that reconfigure the way that we engage with history by listening to local stories and translating them into sculptural forms. Although it’s impossible to faithfully represent someone else’s story, I’m hoping to rediscover traces of the past that have been overlooked. So many dusty narratives remain hidden beneath the surfaces of our built environment. What if they can be animated so that history becomes alive again?

Right now I'm experimenting with a new series of works for a solo show opening in September at Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne.

-

Mason Kimber: Slanted Mansions

by Emma O’Neill

The Urban List, Sydney

October 2018

Raised in an architectural feature home in Perth that was all straight lines, simple shapes and a blurred interior/exterior, Mason Kimber’s work has long been informed by the construction of homes and memories. In his latest suite of works the artist takes his cue from the far messier, tumbledown buildings of Manila in Quezon City, Philippines. The mega-city, twice as densely populated as NYC, has been stamped by Spanish Conquest, shaken by frequent earthquakes, ripened and burst open by never-ending urbanization.

Mason wraps this patchwork of shared space into quiet, cool-coloured sculptural tablets. Appearing like soft-focus surveillance images, the paintings/sculptures cut through the clean lines of COMA Gallery in Rushcutters Bay and are far more interesting than your average holiday souvenir. Thanks for the memories, Mason.

-

-

Slanted Mansions

by Mariam Arcilla

Catalogue text, COMA, Sydney

September 2018

In Slanted Mansions, Mason Kimber presents a new inventory of sculptural tablets, floating fragments, and compositional sketches that preserve the decaying chapters of places and memories in Manila. The story starts in June of this year. Kimber and I visited my hometown of Quezon City, in the ripe howls of monsoon season. Mummified into raincoats, we explored my childhood home, former school, and my uncle’s marble factory—poignant sites that shaped my family’s lives and today continue to decline from the decades-old sway of time, weather, and neglect. Kimber listened to my stories of growing up in this vivacious megacity, which exists within a climate cocktail of earthquakes, super-typhoons, landslides, and volcanic eruptions.

These natural disasters left neighbourhoods in a hotchpotch—slanted homes, tangled gardens, and rubbled walkways. My family reset ourselves many times: we’d replace soaked beds, repair roofs, salvage floating debris, and wash out lava ash from our clothes. Eventually, we learnt to become limber to the dance moves of this ever-shaking metropolis. We painted our homes in cornflower blue and peppermint—colours that behaved as pulsating way-finders during acid rain and electrical brownouts. We erected steel gates to keep floods out. We staked walled perimeters with thorny fields of smashed soft-drink bottles to deter wind-hurled structures, as well as looters. It was here that I developed pre-mourned gratitude for possessions, knowing there was a chance they’d break or float out the door in the next wet season.

In Tagalog, the phrase ‘sumaging lagi sa alaala’ has dual meaning: ‘to haunt a memory’ and to ‘keep a memory.’ It’s similar to this mixed feeling of letting go of an object in your mind mentally, while still being able to touch it physically; a reverse phantom-limb of sorts. The jumbling of memory is a main propeller for Kimber. Before he was a full-time artist, he collected vinyl and hosted radio shows as a music producer in Perth. He spent days hunting down rare, yesteryear vinyl and chopping them up to reconfigure into new sounds.

Today, as a visual artist, he remains faithful to this method, splicing memories and weaving them into new compositions—often while listening to the same songs in the studio. Esteemed music producer Mark Ronson summed it up elegantly: ‘Sampling isn't about hijacking nostalgia wholesale. It's about inserting yourself into the narrative of a song while also pushing that story forward.' In Slanted Mansions, Kimber recorded his personal observations and shared experiences of Manila, and remixed them into a new authorship that paid ode to the legacies of keeping and haunting a memory.

While in Manila, Kimber entombed mnemonic surfaces with sticky coats of amethyst-purple silicon moulds: structural shapes like gates, roofs, windows, and balcony walls, and portable items, such as plants, carved furniture, and heirlooms. Once hardened to rubber, these moulds were peeled off, like escape pods detached from their source, to unearth replicas of fissures and mounds. The shapes are then remastered with gypsum and resin to form odd-edged slab pillows that emanate off walls and clustered fragments that lash around like steep glaciers or bulbous stalagmites; one reminds me of a chocolate bar broken up to share. These works are by no means intricate copies. Rather, they triumph the intuitive and abstract marks of a studio process — sunken edges, rasped patterns, and goosebumped imprints—in the same way that memory fogs and fades through time. ‘My intention is not to recreate the physical exactness of a space or object,’ Kimber says, ‘it’s about capturing their memories and tangible qualities, and turning them into monuments to stories that are worth preserving.

Mason Kimber - Slanted Mansions from COMA on Vimeo.

-

Future Relics

by Mariam Arcilla

Catalogue text, Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

May 2018

Even the most elastic of superbeings, time travellers, have rules to obey. This license to vanish out of rooms and bounce into new eras is restricted by a simple quantum catch: their bodies can move through space and time, but their surrounding architecture must stay behind, in a previous timeline.

How then does one capture the memory of a place, the grasp of it? How can the fragments of a room, a pathway, a building, or a view be smuggled into new memories?

Mason Kimber is anchored by the inbetweenness of architecture and memory: places that serve as timestamps, surfaces that form sentiment, colours that trigger. Born and raised in Perth, the artist moved home several times (as children of divorce often do), before decamping to Sydney a decade ago, where the erratic city rental climate had him hopping studios every year. Kimber has since developed a painting practice that deals with the collision of experienced places — interiors and exteriors that have become sanctuaries for the artist.

For Future Relics, Kimber mines his Bondi studio environment for artifacts, creating impressions from ornamental motifs, limestone columns, bubbled windows, and pavement patterns. They are cast into moulds, along with personal effects like paint palettes, ceramic mugs, plastic particles, and fauna. He then breaks and remixes the pieces with cast archives from past studios. Assembled excavation-style on the ground, they are enshrined as islands of form and texture, through the process of pouring, marking, and setting.

What arises is a new dialect of relics. Bordered, shallow-pooled slabs that rupture, swell, and splinter like maps of a re-envisioned city or a memory puzzle that minces before with now. Presented as wall-based panels, they clasp you into gaze with their skatey gestures, boney curves, and chromatic grouping; they allude to Kimber’s surrounding architecture of historic buildings and the sea. Through his practice, Kimber has found a way, perhaps a loophole, to stamp time and collect a place.

-

Why you need to see...Mason Kimber

by Katie Milton

The Sydney Morning Herald

17th March 2017

As a teenager, Mason Kimber lived in an architectural feature house in Perth. The first residential project by Patroni Architects, Kimber House was immaculate, a concept realised in clean angles, geometric shapes and interior elements that extended as features on the outside of the house. The boundary between the inside and the outside was intentionally blurred.

"This had a big effect on the way I think about space and all the paintings I do. I've realised they're about that threshold – in and out," Kimber says.

After completing his master of fine art (painting) at National Art School in Sydney, Kimber was awarded a residency at the British School in Rome, where his work became entangled with frescoes, an antique painting technique on wet lime plaster.

"It takes seven or eight hours to dry and in that time you can paint into it, and when it dries the painting becomes the wall," he says.

This year, he scored a coveted one-year studio residency with Artspace, and now paints from a spacious third-floor space overlooking Sydney Harbour. Working with an iPad propped on a wall mount next to his canvas, Kimber moves back and forth between the digital and the physical.

"I take a photo of the canvas and put it in Photoshop and collage different sources into the image, then go back and paint it onto the canvas," he says.

Kimber's solo exhibition, Arcades, is his first in two years. The name comes from the Arcades Project, an unfinished collection of writing by German literary critic Walter Benjamin. "They're fragments," says Kimber of his collaged paintings, comprised of samples of smaller paintings, photographs, cheap fabrics, architectural sketches and Roman ruins and motifs. Evolving from his earlier frescoes, now he's excavating an archaeology of his own past works.

"I'm interested in architecture and different shapes, and the way different surfaces and textures can make you feel," Kimber says.

by Katie Milton

The Sydney Morning Herald

17th March 2017

As a teenager, Mason Kimber lived in an architectural feature house in Perth. The first residential project by Patroni Architects, Kimber House was immaculate, a concept realised in clean angles, geometric shapes and interior elements that extended as features on the outside of the house. The boundary between the inside and the outside was intentionally blurred.

"This had a big effect on the way I think about space and all the paintings I do. I've realised they're about that threshold – in and out," Kimber says.

After completing his master of fine art (painting) at National Art School in Sydney, Kimber was awarded a residency at the British School in Rome, where his work became entangled with frescoes, an antique painting technique on wet lime plaster.

"It takes seven or eight hours to dry and in that time you can paint into it, and when it dries the painting becomes the wall," he says.

This year, he scored a coveted one-year studio residency with Artspace, and now paints from a spacious third-floor space overlooking Sydney Harbour. Working with an iPad propped on a wall mount next to his canvas, Kimber moves back and forth between the digital and the physical.

"I take a photo of the canvas and put it in Photoshop and collage different sources into the image, then go back and paint it onto the canvas," he says.

Kimber's solo exhibition, Arcades, is his first in two years. The name comes from the Arcades Project, an unfinished collection of writing by German literary critic Walter Benjamin. "They're fragments," says Kimber of his collaged paintings, comprised of samples of smaller paintings, photographs, cheap fabrics, architectural sketches and Roman ruins and motifs. Evolving from his earlier frescoes, now he's excavating an archaeology of his own past works.

"I'm interested in architecture and different shapes, and the way different surfaces and textures can make you feel," Kimber says.

-

PAINTINGS OF PAINTINGS

by Stella Rosa McDonald

Catalogue text, Arcades, Galerie pompom, Sydney

March 2017

In the Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard writes of the effects of snow upon a house;

The house derives reserves and refinements of intimacy from winter; while in the outside world, snow covers all tracks, blurs the road, muffles every sound, conceals all colors. As a result of this universal whiteness, we feel a form of cosmic negation in action. The dreamer of houses knows and senses this, and because of the diminished entity of the outside world, experiences all the qualities of intimacy with increased intensity.

Bachelard writes of the Winter House in negative, revealing the psychic state of interior space from the outside in. The walls, doors, apertures and corners of the house are thrown into relief by seasonal warmth, cold, closeness and distance. For the dreamer of houses, the foundations are always built upon a semantic equation. We are, as Bachelard so deftly lays out, where we are not.

Mason is on the floor of his studio, casually shuffling through soft piles of hand-drawn sketches as if they are receipts, or quotes (albeit his own). He appears to be looking for—and finding—nothing in particular. He talks while he touches the paper. His process is to flicker—a jarring term he often uses to describe both the quality he is seeking to bring out in the paintings and the way he goes about bringing it—between the material and mannered spaces of architecture, the screen and painting. He wants the final images to flicker too. From the piles of paper quotations, he makes digital collages that form the basis of larger works on canvas, painted in acrylic and collaged with scraps of cheap synthetic fabric sourced from second-hand stores and torn and cut sections of his own painted canvases. He gleans from his own crops.

Kurt Schwitters saw collage as a shortcut between intuition and the artwork. William Burroughs used the cut-up to short circuit language. Freud sorted through our bins, looking for scraps to help us understand ourselves. Virginia Woolf made use of whatever fragments came her way. The connections between hitherto unconnected things, via the accumulation and arrangement of scraps, is what collage—bald and basic—so acutely achieves. In the context of Mason’s work, slicing, splicing, compression and omission are processes that circumvent perception and certainly refer toward the image’s own precariousness and decay.

Each painting is embryonic in the sense that it holds the key to its own potential. Each painting is historical in the sense that it is made from a collection of past parts. By being both the same as and different from versions of themselves in time, these paintings enter a third state—one of alterity—with each being defined by something other than ‘the sameness of the imitative as compared to the original’.

Patterns, lines and relationships are scaled. A section of this one is swapped out for the architectural motif of that. A brick-skin grid from here is forced into a neat companionship with a blue isosceles triangle from over there. A balustrade is just as likely to be made from steel as it is from chalk. The slippages between works make the passage of elisions and ellipses nearly impossible to trace. And these slippages, along with an understanding of Mason’s strategic use of the screen as an aid for process, could inevitably lead to a characterisation of his painting as a type of tab surfing, where information is arrived at through potentially endless hypertextual association. Such a restless search is prone to conspiracy, association and proof as coincidence (Wonderful!), but the budding and burgeoning Rhizome is not Mason’s project. His vernacular glance—directed toward the screen as much as is toward the interior of a book or a room—is not circumscribed by the tabulated screen, but by the colour of his thought.

These works make little distinction between the acts of painting and thinking. They are paintings of paintings. And I am so moved by the insularity of that pursuit.

-

What's the Angle, Mason Kimber?

by Sophie Lanigan

19th March 2017

My interest in architecture is tickled with fancy at the structure of Mason Kimber's paintings, particularly my favourite from his current exhibition, Arcades at Galerie Pompom, Pathway/Patina.

In Pathway/Patina, Kimber has found a way around the inadequacy of paint to create tangible depth by stretching the canvas with semi-translucent layers of the same coloured deep blue fabric. It has a similarly compelling nature to the pigment works of Yves Klein, where you simply fall into the blueness. With a white oil stick he has given us the gentlest of directions towards a vanishing point somewhere on the right, so instead of falling into an abyss, we fall into the painting. At the edge, a pastiche of textural fragments have been cut and collaged to frame the picture - this is the threshold we cross to step inside. Similar to his frescoes there is a slowness about the process of this painting because each fragment glued to the fabric is made at various, potentially unrelated, points in time, so the painting starts not knowing what it is going to be until Kimber corrals it together. Like different architectural details chosen over time and finally appearing all in the same space.

Historically this work has a nearer reach than his preceding suite of frescos. Instead of evidence of renaissance masters, which reared their influential heads when Kimber took residence at the British School at Rome, the architectural theories of Gaston Bachelard and collage techniques of Kurt Schwitters come to the fore. These are refined works; they are clever in their apparent confusion and striking in their technical and logical merit. Mason is a painter’s painter - he’s got a thorough idea, a confident mark and an engaging composition. In her exhibition essay Stella Rose McDonald astutely points out that Kimber is making ‘Paintings of Paintings’. Painterly angles lead us to the point that Kimber is thinking about Painting, and painting about thinking, which is a very good angle to have if you're a painting painter. Paint

by Sophie Lanigan

19th March 2017

My interest in architecture is tickled with fancy at the structure of Mason Kimber's paintings, particularly my favourite from his current exhibition, Arcades at Galerie Pompom, Pathway/Patina.

In Pathway/Patina, Kimber has found a way around the inadequacy of paint to create tangible depth by stretching the canvas with semi-translucent layers of the same coloured deep blue fabric. It has a similarly compelling nature to the pigment works of Yves Klein, where you simply fall into the blueness. With a white oil stick he has given us the gentlest of directions towards a vanishing point somewhere on the right, so instead of falling into an abyss, we fall into the painting. At the edge, a pastiche of textural fragments have been cut and collaged to frame the picture - this is the threshold we cross to step inside. Similar to his frescoes there is a slowness about the process of this painting because each fragment glued to the fabric is made at various, potentially unrelated, points in time, so the painting starts not knowing what it is going to be until Kimber corrals it together. Like different architectural details chosen over time and finally appearing all in the same space.

Historically this work has a nearer reach than his preceding suite of frescos. Instead of evidence of renaissance masters, which reared their influential heads when Kimber took residence at the British School at Rome, the architectural theories of Gaston Bachelard and collage techniques of Kurt Schwitters come to the fore. These are refined works; they are clever in their apparent confusion and striking in their technical and logical merit. Mason is a painter’s painter - he’s got a thorough idea, a confident mark and an engaging composition. In her exhibition essay Stella Rose McDonald astutely points out that Kimber is making ‘Paintings of Paintings’. Painterly angles lead us to the point that Kimber is thinking about Painting, and painting about thinking, which is a very good angle to have if you're a painting painter. Paint

-

Painting Ruins – Ruined Paintings (Acts of art in the frame of cinema and architecture)

by Sam Spurr

Catalogue text, NEW16, 2016

Published by the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art.

When I first saw the paintings of Mason Kimber, I was assailed by images from a film I had seen decades prior and long forgotten. The plot of The Belly of and Architect eluded me at the time – my memory was like a film reel that had been chopped and thrown up in the air; a potent series of screenshots juxtaposing Roman statues, elaborate interiors, Grecian columns and rolls of architectural drawings. The bodies in these images were fixed and mute, subsumed by the spaces within which they posed. It is a film by Peter Greenaway, who is often described as making films like paintings, and beloved by architects for his preoccupation with creative genius. Amongst the ruins of my memory, the film remains as a kind of cinematic collision between architecture and art.

Ruins are fragments; they suggest past and future wholes. In the same way, Kimber’s paintings are fragmentary both in material form and compositional strategy. They hold literal ruins as well as metaphorical ones, with recurring motifs from ancient Rome that serve as semiotic stand-ins for the past. In NEW16, she shows larger works on canvas as well as the smaller frescos on board that he has become known for. Each painting maps Kimber’s own history: classical busts from his residency at the British School at Rome, architectural elements from a childhood home, and cinematic memories from his past works. The surfaces of these paintings hold the ruins of past ideas, as well as the suggestion of future ones. At times opaque shapes collide with one another, only for one to slip between the others as if underwater. Pastels scrape the skin of oil paint, and watercolours conceal and reveal past images. The frescos themselves are in a state of ruin – a struggle between paint and the texture of sand and plaster. These shattered surfaces are suggestive of forms, spaces and figures, but refuse direct narration.

Ruins are fragments; they suggest past and future wholes. In the same way, Kimber’s paintings are fragmentary both in material form and compositional strategy. They hold literal ruins as well as metaphorical ones, with recurring motifs from ancient Rome that serve as semiotic stand-ins for the past. In NEW16, she shows larger works on canvas as well as the smaller frescos on board that he has become known for. Each painting maps Kimber’s own history: classical busts from his residency at the British School at Rome, architectural elements from a childhood home, and cinematic memories from his past works. The surfaces of these paintings hold the ruins of past ideas, as well as the suggestion of future ones. At times opaque shapes collide with one another, only for one to slip between the others as if underwater. Pastels scrape the skin of oil paint, and watercolours conceal and reveal past images. The frescos themselves are in a state of ruin – a struggle between paint and the texture of sand and plaster. These shattered surfaces are suggestive of forms, spaces and figures, but refuse direct narration.

Cinema has been an ongoing source of inspiration throughout Kimber’s short but notable career. In past works this inspiration has taken the form of shifting, ephemeral imagery, evocative of events and atmospheres, hazy and deformed by memory. However in his more recent work, Kimber moves away from correlating painting and photography in the trajectory begun by Gerhard Richter. Instead, a collage aesthetic brings the cinematic in line with Kimber’s fascination with architecture, an interest less in form than in spatial experience. This aesthetic is also what saves the work from sinking into nostalgic representation.

Architecture has traditionally reified photography for its ability to return a building bak to its state as a drawing. In a photo one can focus on a static set of lines and form, devoid of the mess of change and movement brought by bodies and time. In contrast, cinema embraces spatial complexity, taking architecture away from the image and into experience.

Our experiences of spaces to not unwind like a film reel, but instead layer, fold and merge. As we walk through the world, shifting geometries of images collect and accumulate around us in constant transformation. These fragmentary images are not only the ones we’re in, but are made up of other images drawn from stories read, films seen, our fantasies and our histories overlaid.

When I recently re-watched the Greenaway film I discovered that many of my original memories were false – they came instead from other films of had been reshaped from my own Roman adventures.

Kimber’s paintings conjure this phenomenon of experience in a single frame. Vision is not tamed and simplified by a single-point perspective, but multiplied and recombined. The viewer is drawn to ward each painting by a detail, only to move again to reconfigure the whole. The works are installed in order to heighten this process, with geometries extending beyond the frame and onto the gallery wall. A plane of colour sweeps from the wall to the floor inviting you to step forward. Inscribed lines suggest alternative interior on which the paintings have hung, or will hang. This produces an uncanny repetition of interiors that reverberate from the gallery walls and multiply like ghosts into the works themselves.

The ruin is a fetish few can resist. Ruins are open-ended, as if time had paused unsure of wether to go forward or back. The ruin is in itself an invitation to come in and complete it. Kimber’s paintings embrace this quality of unfinished possibilities, and similarly they are a lure to speculation. Like ruins, what is so tantalizing about these paintings is that they make us world-makers, and in viewing them we rebuild them to our own fantasies.

ISBN: 978-0-9943472-2-0

-

Mason Kimber

by Steve Dow

Art Guide Australia

17th April 2015

Tactile yet seemingly fragile, Mason Kimber’s frescos for his first solo show at Sydney’s Galerie pompom provoke contradictory responses: to touch, at the risk of adding to the apparent erosion, but also to protect what is left.

Oltre la Vista – or “beyond the view” – is a poignant play on the slipperiness of memory, feeling and meaning, and Kimber’s daring use of materials and ideas in the frescos in particular succeed by evoking some unnamed nostalgia – not as sentiment but as the pain of an old wound and a lost world.

Six of the 13 works here are an alchemy of pigment on sand and high-calcium lime plaster, the chemical reaction leaving a grainy surface. It seems as though the works have been excavated from a Roman ruin. The plaster forms a ragged, sandy frame closing around abstract images of angular window frames, looking onto distant aqua sea or perhaps sky.

Kimber paints fresh onto the plaster, just before it completely dries, so that the art and its architecture are one. “Fresco is known as one of the hardest mediums to work with,” he says, “but I think the unique effects it produces are worth the effort.”

The artist’s play with our perception was born of an interest in spatial perspective and illusion, stemming from a three-month artist’s studio residency at the British School at Rome. The recurring aqua motif though appears homegrown: he grew up in Cottesloe, Perth, between the Swan River and the Indian Ocean.

The other seven works are oil on canvas. Visually, it’s a contradictory shock, having spent time studying the frescos, to then look at the largest of the oil works, Thinking Slow, Painting Fast, 2015, with its much bolder green background and fragment of a male torso. It’s dominant and demanding of your attention, compared to the frescos’ suggestion of fading light and life.

Oltre la Vista – or “beyond the view” – is a poignant play on the slipperiness of memory, feeling and meaning, and Kimber’s daring use of materials and ideas in the frescos in particular succeed by evoking some unnamed nostalgia – not as sentiment but as the pain of an old wound and a lost world.

Six of the 13 works here are an alchemy of pigment on sand and high-calcium lime plaster, the chemical reaction leaving a grainy surface. It seems as though the works have been excavated from a Roman ruin. The plaster forms a ragged, sandy frame closing around abstract images of angular window frames, looking onto distant aqua sea or perhaps sky.

Kimber paints fresh onto the plaster, just before it completely dries, so that the art and its architecture are one. “Fresco is known as one of the hardest mediums to work with,” he says, “but I think the unique effects it produces are worth the effort.”

The artist’s play with our perception was born of an interest in spatial perspective and illusion, stemming from a three-month artist’s studio residency at the British School at Rome. The recurring aqua motif though appears homegrown: he grew up in Cottesloe, Perth, between the Swan River and the Indian Ocean.

The other seven works are oil on canvas. Visually, it’s a contradictory shock, having spent time studying the frescos, to then look at the largest of the oil works, Thinking Slow, Painting Fast, 2015, with its much bolder green background and fragment of a male torso. It’s dominant and demanding of your attention, compared to the frescos’ suggestion of fading light and life.

The canvas works encourage Kimber’s bolder palette of colours and are more evocative of built spaces and their multiple, angular perspectives. Yet it’s the frescos, with their subtlety of colour and concept, reaching to the natural world, that invite the viewer to linger.

-

Facade

by Liz Chang

Catalogue text, Facade, Artereal Gallery, Sydney

2015

Informed by his recent three-month residency in Rome, Italy, Mason Kimber’s new works are borne from the traditions of fresco painting. Using techniques reminiscent of Pompeian style muralism, Fresco 7 (2015) and Fresco 8 (2015) reveal the remnants of a built space. Kimber constructs layers of sand and plaster to mimic the texture of ancient walls; after the foundational layer is dry, he reworks the composition with sheer and opaque layers of paint to create a trompe l’oeil effect. The eye is fooled by the simulated depth alluded to by shadows and structural forms. Kimber plays with breaking the fourth wall between the work and viewer and draws their eye into the perplexing scene of dilapidated buildings. The tension between the numerous dimensions of foreground and background allows the surface to become interchangeable.

-

Artist Q+A: Mason Kimber

by Tess Ritchie

Habitus Living

30th March 2015

How would you describe your work?

These are some keywords I would use: architecture, spatial perspective, fragmentation, subconscious, associations, memory and painterly abstraction.

Are there certain ideas or subjects you are most interested in?

I’m interested in the idea of ‘architectural memory’. Built spaces, whether they are real or imagined, have the potential to hold certain memories. This idea can be traced back to ancient Greek times before the invention of text, where orators instructed their students to imagine objects within the spatial context of a room in order to help them recall information. Ruins and fragmented buildings in particular have this uncanny potential to create mnemonic associations.

Where do you find inspiration?

These new works stem from a fascination with the various styles of spatial illusion found in Pompeian fresco painting during a recent studio residency at the British School at Rome. The many rich layers of history, architecture and painting that are visible in Rome and in its museums have given me a huge amount of material to work with. The experience of having a studio there for three months will continue to inspire me for years to come.

How does the local landscape and environment feed into your work?

Natural influences often appear unknowingly through the colour choices I make. No matter what subject matter, there always seems to be an element of aqua blue that is used subconsciously. I put this down to the environment where I grew up in Perth. Cottesloe is an area surrounded by water, situated between the Swan River and the Indian Ocean.

Can you talk about your style, what kind of process do you use and how has it developed over the years?

I mainly work as a painter using oils on canvas, but these new works are the result of experimentation with traditional fresco techniques using high-calcium lime plaster, sand and pigments on plywood to form portable fresco panels. Painted ‘fresh’ into the plaster just before it completely dries, they are the products of a chemical reaction that forces the painting to become one with its architectural support. Fresco is known as one of the hardest mediums to work with, but I think the unique effects it produces are worth the effort.

What do you enjoy most about being an artist? What are the challenges?

I have a compulsive need to create and often feel guilty if I’m not making something or developing ideas. My favorite place to be is in the studio. That said, sometimes it’s really difficult to find motivation when things aren’t working. The key is to accept failure as part of the process to creating something unique. It’s often only through the process of doing that progress can be made. Fortunately, I enjoy the challenge.

Advice for aspiring artists?

It’s simple – believe in yourself. Self-doubt is the creativity killer.

http://www.habitusliving.com/community/artist-qa-mason-kimber

-

When in Rome: Mason Kimber’s Fresco Perpective

by Rebecca Caratti

Buro 24/7 Australia

24th March 2015

Flicking between the solidarity of architecture and the illusiveness of memory, Mason Kimber’s newest paintings at once evoke a sense of Italian wanderlust while also exploring the abstract.

In the past year alone, Perth-born, Sydney-based artist Mason Kimber’s CV has had quite the makeover. He was awarded the illustrious National Art School’s British School at Rome Residency, picked up an ArtStart Grant from the Australia Council for the Arts, and has been a finalist in The Substation Contemporary Art Prize, the Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship and the Macquarie Group Emerging Artist Prize. To say that he is fast becoming a favourite among curators and collectors-in-the-know is a massive understatement.

This month, Kimber will be making his commercial solo debut when he will grace the walls of Sydney’s Galerie pompom with the works crafted during his Italian stay. Fascinated by Rome’s Pompeian frescos and ancient structural ruins, along with the uncertainty that human memory allows, the show beautifully plays with texture, light, ideas of architectural and spatial perspective and the romance of the past, resulting in a body of work that is sophisticated, fragmented and softly energetic. Not to be missed.

-

Oltre la Vista

by Nick Tobias

Catalogue text, Oltre la Vista, Galerie pompom, Sydney

2015

A visit to Mason Kimber’s studio is a great experience, full of interesting contrasts and contradictions. The impact of his recent residency in Rome is evident in the work, especially that his time was spent not only with other artists, but architects, archeologists and other academics.

The fresco (as studied in Rome, Naples, and Pompeii) is one of the bridges between architecture and art. Mason Kimber questions the idea of authenticity and what really makes something authentic in these fresco works. Using the layering of objects, colours, frames and shafts of light to draw the viewer into the scene, he leaves the question of whether one has been placed inside or outside. Is one the viewer or being viewed? Although abstract they evoke a spatial quality, one where the architecture is not clearly seen but certainly felt.

Memory is also an important part of these works, not only due to the obvious reference of time, and the physical erosion of the pigments and plaster, but also through information that has been lost as a result. It is interesting to think about how we retain some memories yet forget others, only to remember them again, however not always in exactly the same way they happened. Filling in the gaps becomes a very personal experience and one could argue a creative process – this process certainly helps to take the viewer back in time.

Kimber’s drive to discover the past is found both in his exploration of subject and also through his dedication to past techniques. The technical research and testing to achieve the fresco textures using plaster and pigments has been extensive.

In contrast, the works on canvas offer a multi-layer, multi-framed experience. Although they make reference to the frescos and other classical elements, they are clearly contemporary, using blocks of colour in various shapes and textures with great painterly confidence, taking the viewer into the depths of the work. The idea of missing information, evident in the frescos, appears again but this time in the form of entirely missing figurative elements, figures in relief, elements in shadow.

When we last met I questioned Mason on the purpose of art and he told me it was to explore. One could argue this is one of the central purposes of life itself. The title of the show is Oltre la Vista (Beyond the View) and it is here that the real exploration of life and art takes place.

-

Oltre la Vista

by Sharne Wolff

The Art Life

6th April 2015

Perhaps Mason Kimber’s new body of work Oltre La Vista (or beyond the view) could equally have been titled When in Rome. Inspired by a recent artist residency at the British School at Rome, Kimber’s artistic eye fastened on classical architecture and the frescoes of Rome, Naples and Pompeii. During his stay, he researched, developed and adopted new (old) painting techniques. In this show, just over half of the fourteen paintings are oils on canvas while the remaining group – all titled Fresco (fresh in Italian) – were painted using Kimber’s old-school method of combining pigment with sand, high-calcium lime and wet plaster. Painted direct onto panels, the paint is absorbed by its plywood support giving these pictures their unique texture and muted appearance.

Kimber’s interest lies in visually capturing the traces of memory found lingering in architectural spaces. Using strong lines, blocks of colour and drawing on the icons of classical art and sculpture, Kimber’s compositions are dominated by aquas, marine blues and purples punctuated by small doses of yellow and ochre. Encouraging the viewer’s attention with shifting shapes and floating decoys, Kimber sets up elusive narratives. When it becomes impossible to pin down any single prospect, looking beyond the view becomes inescapable.

-

Stranger at Home

by David Greenhalgh

Catalogue text, Stranger at Home, Archive Space, Sydney

2014

Mason Kimber is concerned with where we come to fool ourselves, and given he has dedicated his practice towards a medium that is all about trickery and illusion it is a pertinent topic to address. Kimber is a painter and he paints on the topic of memory.

Painting, particularly in the West, has dedicated itself towards that difficult to pronounce term tromp l’oeil, which is French for ‘trick/deceive the eye’. Painters strive to create realistic impressions of the world, faithfully rendering what the eye sees into a masterful illusion. A founding myth of Western art is the Greek story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius, two painters of repute who pitted their skills against one another- firstly Zeuxis painted grapes so realistic that the birds would try to eat them. Parrhasius then asked Zeuxis to judge a painting in his studio kept behind a curtain. When Zeuxis attempted to draw back the curtain he realized it was a painting, thus Parrhasius was declared the winner. From Parrhasius on, painters have dedicated a sizable portion of art history since to the art of tricking the eye: painting itself is synonymous with the art of trickery to most people.

Kimber swerves the direction of painting to an altogether more pressing issue embodied within this medium, that is the trick of the mind, specifically memory. When you gaze into one of Kimber’s pantings the first thing to strike you is the torrent of perspectives, vanishing points and rendered shapes, all of which are recognizable yet just beyond your grasp of understanding. You can see an interior here, or a landscape there, yet all symbols of confirmation are either absent of seemingly blurred. They’re like a dream. Now we are part way to understanding what we’re seeing, but the dream like memory that Kimber is recalling on canvas is a symptom of our age: the Screen Memory.

Father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud first theorized the Screen Memory. It denoted a memory that stood for a repressed or traumatic memory, effectively blocking it from recall. This term gathered further significance when a study conducted in Marseille in 1977 by a team of sociologists found that it was common for their subjects to recall a memory of a film as though they were their own.

Kimber constructs his images by piecing together stills from Hollywood movies into a depiction of the ambiguous nature of the human memory where fantasy and reality readily intermingle. In turn, your experience of the painting may too become a reality. These canvases are a trick of the mind symptomatic of modern man delivered to us by a trick of the eye from ancient man. Kimber is an architect of a tromp la memoire.

-

Screen Memory

by Dr. Ian Grieg

Catalogue text, Screen Memory, MOP Projects, Sydney

2013

Since its invention, cinema has been linked to an understanding of how memory functions. Kimber’s paintings explore this link in relation to his own experience.

Freud coined the term ‘screen memory’ to describe the way our earliest memories are created rather than recalled, implicated as they are with later memories, fantasies and desires. And as the recollection of a memory is a creative process, so too is the recollection of an image. In a world in which “reality is always already an image”, the dynamics of memory increasingly find their visualisation through image-based media like film. Contributing to the recurring déjà-vu of contemporary experience, cinema’s simulacral impetus is enhancing our shared collective visual memory. Our inner dialogue with memory works in a similar way to filmic techniques of montage, flash-backs and fade-outs, and filtered images from films become extended memory referents, embellishing the fragmented factualities of personal experience with the artificial and the imagined.